|  |  |

United Kingdom and the world

|  |  |

|

|

|

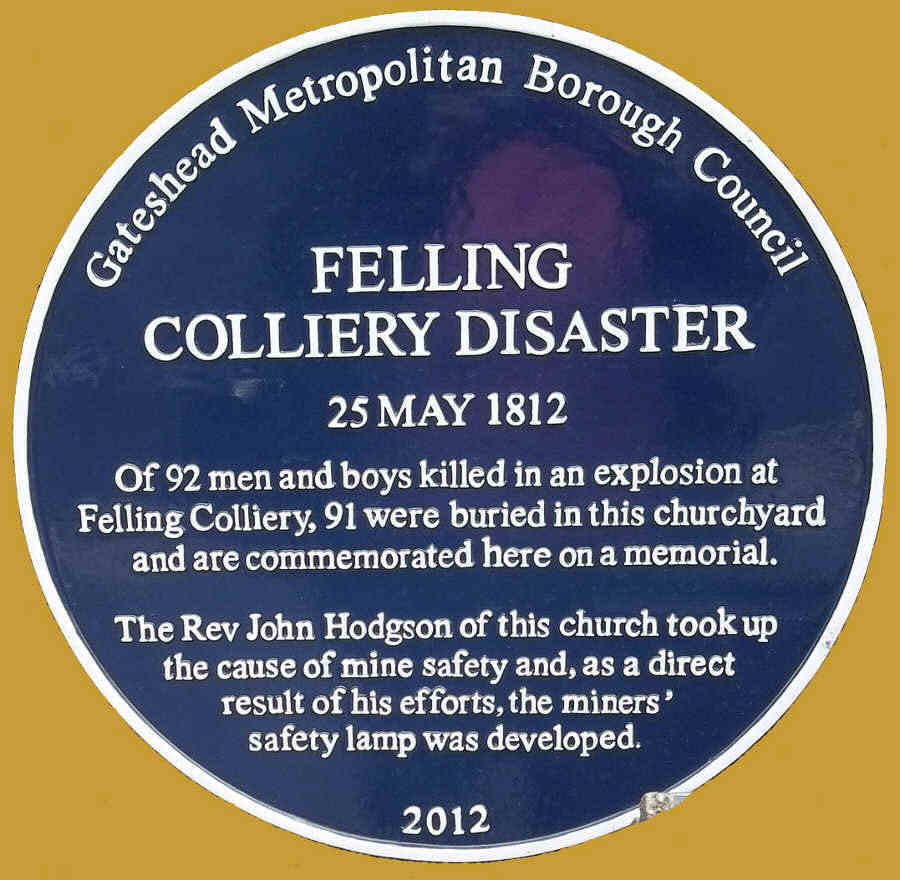

About half-past eleven o'clock on the morning, one of the most tremendous explosions on record in the history of the collieries, took place at Felling, near Gateshead, in the mine belonging to Mr. Brandling, which was always considered one of the most safe in the district. Nearly the whole of the workmen were below, the second set having gone down before the first had come up, when a double blast of hydrogen gas took place. A slight trembling, as from an earthquake, was felt for about half a mile around the workings ; and the noise of the explosion, though dull, was heard to three or four miles distance, and much resembled an unsteady fire of infantry. Immense quantities of dust and small coal accompanied these blasts, and rose high into the air, in the form of an inverted cone. The heaviest part of the ejected matter, such as corves, pieces of wood and small coal, fell near the pits; but the dust borne away by a strong west wind, fell in a continued shower from the pit to the distance of a mile and a half. In the village of Heworth, it caused a darkness like that of early twilight, and covered the roads so thickly, that the footsteps of passengers were strongly imprinted in it. The heads of both the shaft frames were blown off, their sides set on fire, and their pullies shattered to pieces ; but the pullies of the John Pit gin, being on a crane not within the influence of the blast, were fortunately preserved. The coal dust ejected from the William Pit into the drift or horizontal parts of the tube was about three inches thick, and soon burnt to a light cinder. Pieces of burning coal driven off the solid stratum of the mine were also blown up this shaft. As soon as the explosion was heard, the wives and children of the workmen ran to the working pit ; wildness and terror were pictured in every countenance. The crowds from all sides soon collected to the number of several hundreds ; some crying out for a husband, others for a parent or son, and all deeply affected with an admixture of horror, anxiety, and grief. In this calamity ninety-one men and boys perished. The few men who were saved, happened to be working in a different part of the mine, to which the fury of the explosion did not reach. After the mine had been made air tight for about six weeks, to extinguish the fire, it was again opened, and on the 8th of July the workings were entered, and the first dead body found. From various obstructions, the last of the bodies (some of whom were under six or seven feet of stone) was not found until the 19th of September. All these persons (except four, who were buried in single graves) were interred in Heworth chapel-yard, in a trench, side by side, two coffins deep, with a partition of brick and lime between every four coffins. In commemoration of this catastrophe, a neat plain obelisk is erected, nine feet high, fixed in a solid stone base. It has four brass plates let into the stone on the four sides, on which are inscribed the name and age of each of the ninety-one sufferers alphabetically arranged. Source: Local Historian's Table Book of Remarkable Occurrences connected with the Counties of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, Northumberland and Durham by M. A. Richardson. It was published in five volumes in 1844. |

|